“Up until now, the biggest difference between being a journalist in Hong Kong and mainland China was that there is such a thing called ‘illegal news coverage’ in the mainland while covering the news in Hong Kong had always been a right,” said Eric Poon, associate professor of practice at the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and a former producer of [RTHK’s] Hong Kong Connection, which has been covering news in mainland China for many years.

During its colonial era, Hong Kong enjoyed a relatively free and open environment. After its transfer of sovereignty in 1997, Hongkongers remained protected by the Basic Law. Hong Kong reporters have continually relied on this special identity to travel all over China and report the changes occurring within to the outside world. Many Hong Kong journalists who cover mainland news said that even if they encountered dangers locally, they felt a sense of relief once they had crossed the Shenzhen River.

Times have changed. After the implementation of the national security law in Hong Kong, there does not seem to be much difference between the two sides of Shenzhen River. Is there still space for Hong Kong media to cover news? What risks must journalists bear in the future?

Stand News interviewed multiple senior correspondents in China as well as former journalists. Some believe that the current situation has become more desperate than the Tiananmen Square Massacre but still want to wait and see in hopes of dancing on the proverbial knife’s edge. Some remind the reporters not to self-censor and to better equip themselves to keep reporting. Others candidly express that fear is pointless as it is “impossible to know where the line is drawn. You may as well continue as before and do what we know well.”

Bottom Line: Don’t be Reduced to a Political Propaganda Mouthpiece

On 21 May, the National People’s Congress (NPC) announced the authorisation of the NPC’s Standing Committee (NPCSC) to enact the Hong Kong national security law. The sky that afternoon was as dark as the night in Beijing. Torrential rain, thunderstorms and even hail hit the city. Severe thunderstorms also befell Hong Kong that day. K (alias), a veteran correspondent in China, was at his Hong Kong office at the time. He felt nothing when he heard the news and only wondered why there was a single vote against the motion. “Actually, with the Anti-ELAB movement last year and the CCP’s [Chinese Communist Party] Fourth Plenum on top of that, it’s expected.”

Well-versed on China’s political climate, K was well aware that, under these circumstances, the Hong Kong national security law was just an interlude that would occur sooner or later. “Stuck in the same sinking boat, Hong Kong will definitely be destroyed. Ever since China became ‘powerful’, it’s obvious that this trend would appear… So it wants a [Chinese] Communist Revolution, how can Hong Kong be tolerated? What’s more terrifying is that the Communist Revolution previously tolerated Hong Kong because it was poor and had no money. Now that the nation’s power has grown, this kind of stuff is even more frightening than before.”

K started his career right at the beginning of China’s Reform and Opening. He covered news on the special economic zones, experienced Deng Xiaoping’s economic reform, witnessed the drafting of the [Hong Kong] Basic Law and the Tiananmen Square Massacre. Until Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao took power, China’s trajectory seemed to be heading towards democracy and freedom. Who knew that the rise of Xi Jinping in 2012 would lead to an abrupt turn for the worse? K laments over how the current situation has become more “desperate” than 4 June 1989, “Now that he took power and tells everyone to learn the Communist Manifesto… you know you’re going to die. It is totally in the style of fundamentalist Soviet communism.”

K also points out that journalists on assignment in China have always seen Hong Kong as a “safe haven”. They believe they have greater freedom of the press under the protection of Hong Kong’s legal system. “If you overstep (the mainland’s red line) and are charged [with a crime], you may feel safer in Hong Kong. But once the HKSAR government implements (the national security law), even Hong Kong will not make you feel safe.”

K, who works at the management level, says that his colleagues have genuine concerns about the national security law but problems with their assignments have yet to arise. He thinks that journalists have to take their personal safety into account while working. The enactment of the Hong Kong national security law, he believes, must have caused a “chilling effect” in the local media. “Is Taiwanese news off-limits? Is news about the [Taiwanese] Democratic Progressive Party off-limits? Are Xinjiang’s re-education camps and the rift over Tibet off limits?”

“I won’t set a limit. If it must be like that, I would rather not work.”

K makes it clear that his bottom line is not to speak against his own conscience and become reduced to a political propaganda mouthpiece. “It gets depressing at times. Being this far set back, I might not think about how to report more news at all, but how to speak with a clear conscience. It’s not just about being a journalist. It’s about basic human principles. Otherwise, why not become someone else’s publicity tool?”

He also points out that journalists are used to be able to contact East Turkestan independence movement organisations or supporters of Tibet and the Dalai Lama for the latest local news. Even though details with respect to anti-sedition laws were not yet introduced at the time the national security law was enacted, he is still concerned about overstepping the red line. “These kinds of cases touch on ‘subversion’ and ‘secession’ crimes. Like the crime of ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’ (see note 1), it can be extended indefinitely. Often, the decision to prosecute is based on politics.” He also uses the live broadcast Liu Xiaobo’s memorial service in mainland as an example. K admits that broadcasting sensitive material in Hong Kong may one day transgress the red line.

As for the situation in mainland, many actions that should not qualify as “subversion of state power” still end up being tried as such. “Do you believe that the 709 (crackdown)(see note 2) was [related to] subversion?” K asks rhetorically. As part of the crackdown, human rights lawyer Wang Quanzhang was sentenced to more than four years in prison for “subversion of state power”. Afterwards, the agency that K worked for would frequently send reporters to accompany Li Wenzu, Wang’s wife, during prison visits. Each time, they had to talk about how to coordinate. “In the eyes (of the government), we are likely one of them so the line is extremely blurred, especially in the mainland.”

Journalists reporting in mainland were arrested and imprisoned in China in the past, like Ming Pao reporter Xi Yang. He was convicted of “spying and stealing state secrets” in 1994 and was sentenced to 12 years in prison. In 1997, he was released on parole. The Straits Times correspondent in China, Ching Cheong, was charged with espionage at the beginning of 2005 after obtaining a manuscript of interviews with the late Zhao Ziyang. He was sentenced to 5 years in prison and was released in 2008. K reflects on his profession of having to jump through hoops over many years. This time, there are no previous cases for reference [under the Hong Kong national security law]. “You can only refer to fellow colleagues in the mainland. They were either arrested, fled or dead.”

K is not afraid to say that the worst-case scenario is that the news organisation where he is employed will “close up” but he speculates that, at least at the beginning of the implementation [of the national security law], there would be little impact on reporters’ news coverage. He likens news assignments in China to “dancing on the edge of a knife” and “walking on a tightrope”. Now that the “safe haven” of Hong Kong is on the verge of shutting down, reporters must change tack and carefully explore the limited space in which they can report. “Now that the blade is thinner and the tightrope is sharper, you have to choreograph a new dance and think about how to walk the tightrope, unless you no longer work. But if you do, you will have to explore new ways. This is a totally new situation that I’ve never encountered in my decades of work.”

Professionals: Be Water, Be Versatile

Eric Poon was a senior producer of Hong Kong Connection who frequently travelled back and forth to mainland to film sensitive livelihood and political issues, documenting the social changes between Hong Kong and mainland. At the end of 2012, he left RTHK for the Chinese University of Hong Kong. He currently works as an associate professor of practice at its School of Journalism and Communication.

In the 1980s, the Sino-British negotiations on the future of Hong Kong opened the door for the journalists in Hong Kong to gather news from the mainland. More often than not, they represented Hongkongers in raising questions about the future of the city with government dignitaries. Such questions were only made possible by the “protective talisman” that was their “foreign correspondent” status.

Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour uncovered the prelude to China’s economic reform. Poon went to Shenzhen, Shekou and other special economic zones to report about Hong Kong businesses investing in mainland factories and the livelihood stories between the two places. Considered “illegal news coverage” without official approval by the mainland officials, his many years of entry to mainland to gather stories required formal applications with the Hong Kong Liason Office (i.e. Xinhua News Agency at the time). These applications provided heavy-duty protection if fault was found and allowed him to explore all avenues of reportage. During the era of Jiang Zemin and the Hu-Wen administration, China was relatively relaxed about media coverage. “They weren’t completely rigid. Sometimes, they (government officials) would say, ‘right now is not good, don’t come over yet’… Around the time of June Fourth (anniversary), there’s no point in applying to report in Beijing because everyone knows what you’re trying to do… The internal dynamic is: if you don’t cause trouble, I won’t cause trouble either.”

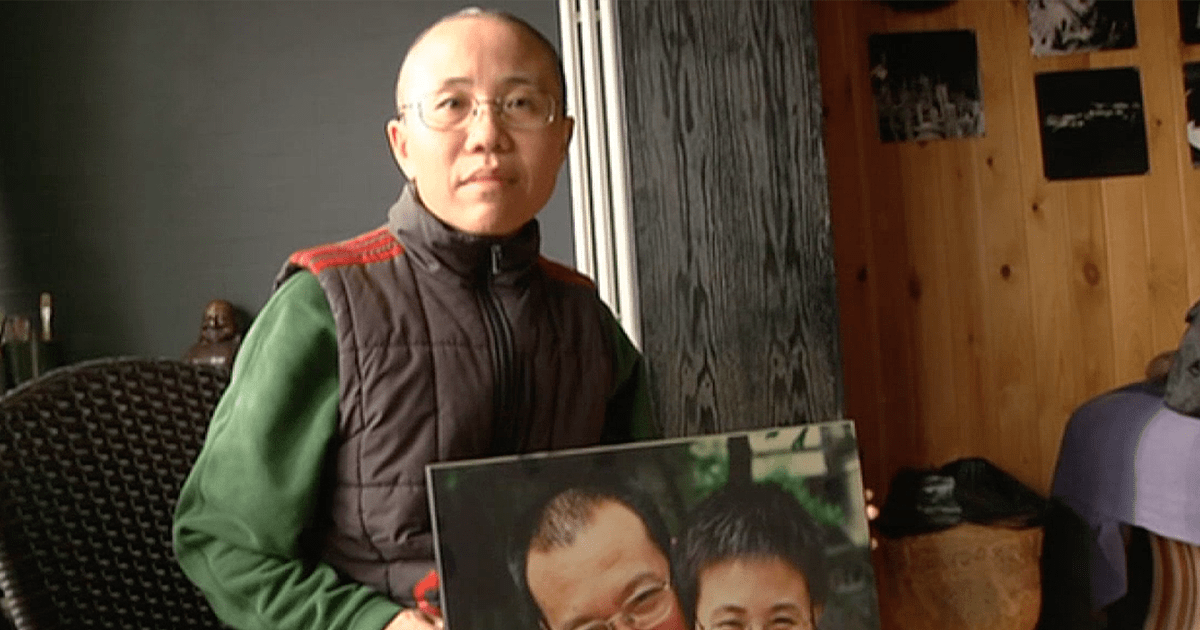

In addition to people’s livelihood stories, Poon often covered politically sensitive topics in the mainland under very narrow restrictions. An example was the jailed 2010 Nobel Peace Prize laureate, Liu Xiaobo, and his wife, Liu Xia, who was placed under house arrest. Poon looked for a middle-man to make contact, but they evidently had no opportunity to reach Liu Xia. When asked about the educated dissident, Chen Ziming, they said there was “a tiny bit” of manoeuvrability. Based on these words, Poon headed straight for the mainland. He successfully avoided public security and weaselled his way into interviewing Chen Ziming, Guo Yushan, Zeng Jinyan and other dissidents. Poon’s record of the events went on to win the Hong Kong Journalists Association’s Human Rights Award; the news boosted the morale of dissident circles.

Poon doubts that “foreign correspondents” would retain their protections after the implementation of Hong Kong national security law. “When (the CCP) increasingly emphasises ‘one country’, you’re no longer a ‘foreign correspondent’ but a regular journalist under ‘one country’.

“Are your actions now considered ‘picking quarrels and provoking trouble’? Will I get screwed over for ‘inciting subversion of state power’ through the national security law? … A dreadful question of this day and age is whether or not this type of interviews are still possible in the mainland.”

He advises reporters in Hong Kong not to limit themselves first. “Self-censorship works. The point is to make you guess the rules of the game. It’s like a boss who doesn’t clearly specify what you’re not allowed to do and just says, ‘Be careful. Sometimes you need to be wary to keep your job.’ If you have to pay rent, you’re going to start guessing: what you can do, what you can’t do… naturally, you’ll end up doing more work.”

Poon describes that common sense, professionalism and ethical values have become distorted in this era. Reporters need to “be water” and become more versatile in response. Besides raising reportage quality, preserving independent thought and investigation work, he makes some other suggestions, “For example, build your social capital or join forces with your peers. ‘Be water’ is all about that.” The goal is to stand firm our ground and keep reporting.

When the situation takes a turn for the worse, each person will need to reflect on their bottom line in the end. “It seems that we have quite literally experienced what Yin Haiguang described in [his book] The Meaning of Life. Each person needs to contemplate… the situation in Hong Kong, its sense of helplessness is far beyond my imagination. I have never seen this before.”

Forbidden Areas: Political Leaders’ Privacy, Military Affairs, Economic Insider Knowledge

Jack (alias), a former senior Chinese division journalist, has been covering news all over China for more over a decade. He describes that many of the red lines reporters cross tend to be “unexpected”. For instance, reporting national statistical figures can violate the National Security Law at any time. An example is when Le Keqiang mentioned that the “monthly income of 600 million people was barely a thousand yuan” at the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference. This information had the potential to draw associations with the CCP’s internal discord. Should a reporter document this? “The band-tightening sutra(see note 3) will invariably get tighter.”

He indicates that for the owners of mainstream media organisations or businesses are their primary concern. If relatively sensitive news – like the Panama Papers from a few years ago – reappear, he fears that opportunities to report will drastically decrease after the law’s enactment. “After its legislation, journalists will have much to take into consideration. If you want to fulfil your duty as a journalist, a knife will be on your neck for a long time. They’ll make a few cuts whenever they want.”

The national security law does not even have to directly harass journalists. Interviewees and relevant figures can be targeted to indirectly obstruct the interview. As an example, when interviewing for the case of Li Wangyang, “they didn’t bother the reporter, but those beside him [Li]. They dragged them to sit on tiger chairs(see note 4). Didn’t this affect the news collected?” Another instance was when the news agency Jack worked for live-broadcasted Liu Xiaobo’s burial at sea after his passing in 2017. Afterwards, at least 13 people were arrested in the mainland. Did this overstep the red line of “national security”? It was never specified.

Jack believes that after the implementation of the national security law, amongst the forbidden areas the most important to the media will primarily be political leaders and their privacy followed by China’s military affairs and economic insider knowledge. In his eyes, the Causeway Bay Books incident had trodden on the “red line”. “The privacy of political leaders and matters concerning their family members overseas have become an issue of national security because it involves contradictions within the party and stability within the regime. The stability of the regime is national security.”

Jack laments that journalists in Hong Kong will soon suffer the same fate as the human rights lawyers in mainland, “dancing with shackles on their feet”. “If (the CCP) forces you to dance, you must dance within these confines.” He predicts that the substance of the news in Hong Kong will diminish over time. In particular, the amount of news involving political figures, commercial bigwigs and collusion between the government and businesses will dwindle. Even investigative reports will decrease, “like Lantau Tomorrow [Vision], which involves Chinese-funded institutions among which are some powerful insiders. Are you going to report that? And if you do, you may implicate yourself in the national security law.”

When the Hong Kong national security law comes into effect, what advice does Jack have for currently employed and student reporters? He stresses the importance of following one’s conscience to do as much as possible. “In these dark times when even the candle is dim, the most important thing is to not let its fire go out. Eventually, you will see the end of the tunnel. The global situation has changed beyond our imaginations. We are facing the world’s biggest challenge since World War II. Compared with the Soviet’s 1991 August Coup and the Revolutions of 1989, this is a much more significant juncture… In this tiny place that is Hong Kong, each reporter must do all they can to not let this feeble flame extinguish.”

In the past two or three decades, Hong Kong served as a major “window” into thornier news subjects on the mainland. Jack mentions that the era of the national security law could see Hong Kong journalists assimilating and becoming more like their mainland counterparts. They would essentially export the news – gathered anonymously and passed on to foreign agencies or foreign media to release. “Exclusivity is no longer a priority for the media with a strong sense of duty and for those journalists who are in pursuit of justice. Freedom of the press is about right or wrong and exclusivity is no longer relevant.”

Frame of Mind: Pessimistic, but Persevering in One’s Duty to Report

Alvaro (alias) is a mainlander and has been working in the Hong Kong media industry for five years as a journalist in the mainland Chinese division. He remarks that China has prioritised its safety over everything else. Ever since Xi Jinping rose to power at the 18th National Congress, there was a definite shift in the CCP’s foreign policy on Taiwan and even their hands-off approach to Hong Kong. Add that to the Anti-ELAB movement last year and the appointment of Xia Baolong, as well as the overhaul of high ranking officials in the Hong Kong Liason Office and the Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office, there was actually a lot of foreshadowing leading up to the national security law.

He believes that the remediation of Hong Kong is just the first step; Taiwan is next in line. “China has clearly become more politically restrictive in the past few years. They can’t tolerate the type of street protests and political expression seen in Hong Kong… They’re making it explicit: Hong Kong is a Special Administrative Region under one country. It holds no special privilege, especially in politics.”

In his view, the attitude behind the CCP’s heavy-handed mandate of the national security law is to suppress Hong Kong. The “harshness” of its written words is not as important. “The way the provisions is written won’t change the CCP’s relentless pursuit for total control and the destruction of ‘one country, two systems’.” The CCP never follows its own rules, in any case. Even if the law is written to agree with Basic Law and human rights protections, they can still interpret or re-write it to meet their needs… Don’t forget that Beijing’s legislators and political leaders never keep their promises.”

Alvaro is blunt about his pessimism towards the age of the national security law because the regime’s way of suppressing human rights activists and lawyers may have nothing to do with the national security law. Majority of the charges pertain to “tax evasion, unlawful business operations” and other types of financial crimes. Since its legislation, he believes that even if the exposure of Hong Kong’s dark side and injustices is not politically motivated, the authorities will still deem such action as “antagonistic” to allow for its suppression. Pan-democrats and localists will likely be targeted first, followed by the legal community and the media.

Alvaro points out that society in Hong Kong is used to being open and free. Its correspondents in China know “the state of the country” better than its Western counterparts. The news in Hong Kong on China has always been an important “window” that allows the West to peer into the nation’s changes. Although there has yet been any tangible impact, this special role has already turned to dust.

He also indicates that the media in mainland has been wilfully reporting and commentating on the Anti-ELAB movement as it was happening, essentially clamouring for attention. With the termination of RTHK’s show, Headliner, he holds a bleak view of the future of Hong Kong’s media. “The CCP keeps a close eye on dominant discourses… it will not (take action) overnight, but gradually infiltrate.”

As he frequently shuttles between Hong Kong and mainland to gather news, Alvaro stresses that he could not reveal too much detail to protect the safety of his fixers and interviewees as well as his family and himself. However, he does mention that he has been beaten up, stalked, monitored and deprived of his personal freedoms while working in the mainland. The people responsible were not necessarily part of national security. Sometimes, they did not wear uniforms or show their credentials. They would only verbally claim to be the police, making it difficult to verify their identities. He also encountered situations where the interviewee or fixer was arrested for agreeing to work with him. Cyberattacks, telephone bugging, location tracking and other surveillance methods have occurred countless times.

Even with these experiences, Alvaro underscores that the CCP never talks about rules. Even if reporters censor themselves in fear of the national security law, it would not make the media any safer. “The CCP has always seen it as them versus us; there are no nuances.” He feels that in the face of the regime, journalists should uphold professionalism and not shrink back in fear.

However, he has a bottom line as well – if his family members in mainland get harassed, he will consider changing his line of work. “There’s no other way. I still have to work and can’t think too much, but I also know I need to protect myself… I must mentally prepare for the worst. But worrying alone doesn’t do anything because you still have no way of knowing where the red line is drawn. Fear will only tie you down. It’s not the same as before. Just keep doing your work well.”

Source: Stand News, July 2020 read the original article in Chinese here

Translated by Guardians of Hong Kong

Images: copyright of their respective owners

Notes:

Note 1: Picking quarrels and provoking trouble is a crime under the law of the People’s Republic of China and carries a maximum sentence of five years. As this is an ill-defined crime, it has frequently been used as an excuse to arrest human rights activists, civil rights activists, and lawyers in China, and hold them in detention pending more serious charges such as inciting subversion of state power.

Note 2: The 709 crackdown was a nationwide crackdown on Chinese lawyers and human rights activists that began on 9 July 2015.

Note 3: The band-tightening sutra is in reference to how Tang Sanzang disciplined Sun Wukong with a tightening headband in the Chinese classic, Journey to the West.

Note 4: A tiger chair is a torture device used in Chinese prisons.